Whose Kingdom Come?

Gospel of Luke, chapter 11

Welcome back to our study of the Gospel of Luke, progressing more or less a chapter a week. After taking a few weeks off for a summer break, we resume at chapter 11.

If you are just joining this series and are curious as to why this is taking place at this particular moment in the history of the world, check out these previous posts which explain the motivation and method we’re pursuing.

*******

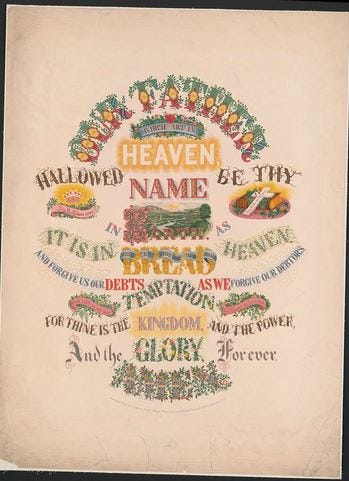

Chapter 11 in the Gospel of Luke consists of a somewhat random collection of materials, mostly things Jesus said in various settings to various audiences. For today’s post we will focus on Luke’s version of the Lord’s Prayer (also known as the Our Father). I have typed out the relevant verses below.

Father [Pater, not Abba] May your name be revered; may your kingdom come. Give us our [epiousios] bread. Forgive our sins as we forgive those indebted to us. Do not let us be tested.

Text and context:

We’ve already observed that the notion of ‘kingdom’ and ‘kingship’ is more or less baked into the social structure of first-century Israel, living as it was under Roman occupation. Centuries earlier the Israelite nation had asked Yahweh for a king instead of being led by judges, teachers, priests, and prophets. Even after it was explained to them that kings would only exploit and abuse their people, they insisted, and the rest, as they say, is history.

My contention is that by Jesus’ time he had no choice but to use the language of empire as this was simply how the people understood the structure of human societies.

And yet, we know that he rejected the idea of being anyone’s king (see Mt 20:25-28, Jn 6:14-15, Jn 18:33-37), preferring to step away from ‘kingship’ and defer to his Father’s, that is, God’s, direct authority. Notice, for example, how the conversation between Jesus and Pilate in the Gospel of John circles around whether Jesus is some kind of ‘King of the Jews,’ a title which Jesus avoids as adroitly as he can. *

Reading back and forth:

Luke’s version of the Lord’s Prayer is brief to the point of being terse. There are no references to heaven, either ‘who art in heaven’, or ‘on earth as in heaven’. These are from the version in Matthew, who uses heavenly language a lot. In both Luke and Matthew we are advised to address God as Father, pater, not the over-familiar Abba, which only Jesus uses in addressing God. (So much for all those sermons on how we get to call God ‘Abba.’) For the rest of us, then, God is prayed to neither as intimate ‘daddy’ nor Sovereign Lord or King of the Universe, but as the head of the household, the one to whom we look with reverence and respect.

Reverence for God’s name is the critical first petition. Here God’s name stands for God’s being. Jesus is telling his people that God’s holiness, God’s intention for the human community is maligned and abused by any who take the Divine Name in vain. To be specific, by those who, then as now, claim a divine mandate for their abuse of others.

To follow that first petition, then, with a prayer for the ‘kingdom’ of God is to echo that initial request that the human community be restored to God’s original vision of justice, compassion, and equality.

Reading forward, we find additional insight into this ‘kingdom’ of God in Luke, chapter 22. David L. Tiede, in his commentary on Luke, uses the phrase, ‘sovereignty of service,’ in his discussion of this later chapter. Here Jesus is explaining the nature of leadership in his new community to those who are gathered with him the night before his death. He has just shared the bread and cup with them, declaring them to be his own body and blood. He wants his inner circle to understand that leadership in this new society that he is calling forth does not involve conventional ‘greatness,’ or power over. It will be embodied in the practice of kenosis, the pouring out of self for the benefit of others.

I quote now from Tiede: “This passage [Luke 22:25-27] is an ethical policy statement which is grounded in the Christology of Jesus as one who serves, which in this context probably refers to the role he has just played in the meal as host and server” (pp. 384-5).

The last petitions in the Jesus Prayer are for bread, forgiveness, and to avoid the ‘time of testing.’

As long as we’re connecting chapters 11 and 22, might the reference to bread there be the bread of Christ’s Body? The adjective for the bread isn’t ‘daily’ at all, and sadly it appears nowhere else in Scripture, so we don’t have much to go on. But epi means over or above, and ousios means being or substance, so perhaps this is the ‘bread of higher being’, or the ‘bread of becoming’, something along those lines. At any rate, I don’t think it’s about physical sustenance; I think we’re talking about sustaining life at another level.

And what role does mutual forgiveness play in this sort of kingdom? Benevolent pardon for offenses real or imagined was the stock in trade of the higher-ups in the ancient Near East. In this time and place, forgiveness only went in one direction – from the top down. The idea of forgiveness as a function of mutuality, of equality between forgivers and forgiven would have been revolutionary.

And that ‘test’, that trial that we beg to be spared, might that be the all-too-human impulse to power? The mistaken assumption that we know what God’s kingdom should look like, and therefore that we are commanded to put that kingdom in place, by any means possible? I suggest this ‘test’ is as good a temptation as any for Jesus to caution his followers against. Most likely more important for the advance of God’s way of being than the more prosaic temptations against, say, a few of the Ten Commandments.

Given everything we’ve read so far, I simply cannot imagine that the ‘kingdom’ Jesus is talking about, here in chapter 11, in the earlier passages on kingdom and kingship, and later with his disciples at the Last Supper, bears any resemblance to anything his listeners would consider an earthly realm or dominion. This Community of Grace is kenotic, forgiving, grounded in service and in God’s own holiness, something never quite imagined before and therefore immensely challenging.

So what?

So what do we do with all of the kingdom language in the Bible? When the gospels put words like king, kingdom, or kingship, on Jesus’ lips, I am inclined to put quotation marks around them. In this way I hope to help folks hear the words differently - with that slight emphasis that says, ‘…if you must call it a kingdom…, but couldn’t we find a better word?’

Sadly, the substitute words don’t work all that well. Realm, domain, kin-ship, all are well-intended, but the fact remains that a lot of the Christian Canon deals directly with the contrast between Jesus’ new community and the ways of empire. And substituting something else for ‘king’ and its derivatives diminishes that tension, a dynamic that, I believe, is essential to understanding Jesus’ message.

The challenge of keeping the kingdom language is that it becomes familiar, and eventually comfortable, and in the long run, it feels inevitable that we believe we have signed on for some sort of regime with flags and parades and Dear Leaders who are ready to do what kings have done throughout history, and then we wake up one day wondering how THAT happened!

One way to stave off this slide into chaos, perhaps, might be to re-write this prayer, the prayer of Jesus, into something a bit fresh, something closer to Luke’s terse, straightforward version, dropping the too-familiar heavenly references and ‘daily breads’, and kingdom-power-glory language, just to shake up our sense of what this prayer is actually asking for. (Go ahead, try it for yourself.)

Perhaps our next step, then, will be to ask ourselves whose ‘kingdom’ are we really seeking, and to remember that Jesus was and is bringing a whole new reality to birth, a new creation of sorts, and that 2000 years into this project, we are very much not done!

* Fascinating - a Google search for instances in which Jesus rejects the idea of kingship produced a thousand websites insisting that Jesus was indeed a king! Some things never change….

Reading this felt like watching someone gently detonate centuries of imperial theology with a smile and a PhD. Thank you for reminding us that Jesus didn’t come to found a regime but to unravel one. The “kingdom” wasn’t a reboot of Caesar’s playbook. It was a jailbreak from the whole system.

I love the idea of putting “kingdom” in quotes. Might as well put “church” and “Christian nation” in them too while we’re at it. If the prayer of Jesus is really about mutual forgiveness, daily becoming, and sidestepping the ego’s power-hungry tantrums, then no wonder empire has always tried to make him into a mascot.

Grateful for this lens. Less crown, more towel.

Rev. Beth, thank you very much for your insights on the Lord’s Prayer & for your invitation to rewrite it! For many years, I have used it as the beginning of my morning prayers & evening prayers, & little by little, over the years, it changed.

For a while, “Father” was “Father/Mother” (or “Mother/Father”), but I think of God as more than a parent, or teacher, or pastor, etc. — to me, “God” is both familiar & all-inclusive. So I begin “O God, Lord of Love & Peace & Heaven, hallowed be thy Holy Spirit.” I regard Heaven, Love, Peace, & Holy Spirit all as aspects of God, with Holy Spirit as the aspect of God that people welcome into their hearts & through which they communicate with God.

I too wrestled with the word Kingdom & didn’t like any substitutes, so I think of Kingdom as a worldwide spiritual community that also includes a spiritual Heaven. I like your understanding of “bread,” “test/temptation,” & mutual forgiveness — all 3 of which I have pondered, but you gave me new insights.

My favorite part of your article was about Jesus teaching the disciples what kind of leadership their community would need — “it will be embodied in the practice of kenosis, the pouring out of self for the benefit of others.” 🙏